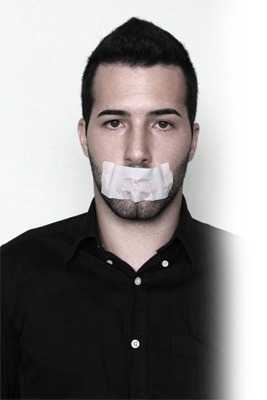

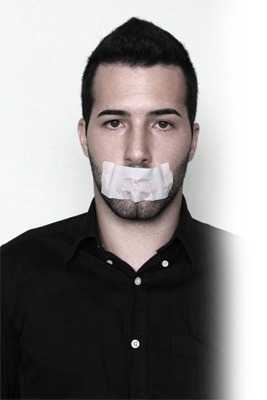

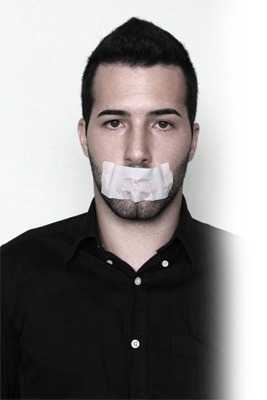

Our gag reflex is a natural protective automatic response designed to keep us alive. It keeps us from allowing any foreign object from going down our throat. It’s one of many survival responses, like jerking our hand away when we touch something hot. We don’t think about gagging; it just happens. Have you ever gagged when having x-rays taken? This is not pleasant.

The pharyngeal reflex or laryngeal spasm activates the gag reflex when something touches the back of the throat, roof of the mouth, tongue, or uvula areas. The tissues constrict in the back of the mouth, which causes a person to gag or feel like throwing up. Many people become concerned when the gag reflex activates, and this makes them feel uncomfortable or nervous.

The gag reflex starts in the first months of life. If the infant’s brain perceives something that’s too lumpy, the hypersensitive reflex activates. Once the infant starts to eat solid foods, the gag reflex diminishes and is less important for survival, unless, of course, a bitter taste is detected and interpreted as dangerous or poisonous. The bitterness will cause someone to vomit and eliminate the hazard immediately. Cotton rolls can also activate the gag reflex.

Patient perception

Some people have a terrible time preventing their gag reflex from activating. This is embarrassing, and they don’t really know why it’s happening. Gagging can be a physiological fear of losing control by vomiting. Some people can see the x-ray holders coming toward their mouths (it’s not even in their mouths yet) and they start to gag. As dental professionals, this can be frustrating, time consuming, and scary. I have told my patients that if they throw up, I’ll be next. I’m a “sympathy gagger.” However, we should offer our patients who gag encouragement, patience, and a positive attitude.

I came up with my article topic when one of my myofunctional patients visited a dentist for her prophylaxis and new-patient examination. When she returned to her therapy appointment, she told me that she went to her dental appointment, but because she had a sensitive gag reflex, they told her to see another dentist. They actually dismissed her from their practice! I was flabbergasted! This patient truly has a severe gag reflex. The dental team did not understand how to handle or temporize the situation. Aren’t dentists always looking for new patients? What do you think this patient will have to say about that office? Negative publicity will not grow a practice.

As a prevention specialist, I felt so bad that she was turned away because of a problem she could not control. So we discussed ways to eliminate her gag reflex. She has a narrow palate and small mouth. We started some remedial activity. The most successful technique was using a small graham cracker placed between her tongue and mandible. She was able to tolerate this and did not gag.

Placing that huge x-ray holder in a little mouth is a challenge for both patient and dental professional. There are other ways to collect radiographic records, such as a panorex, child-size sensors or films, or piggyback bitewing tabs on the sensor to move it toward the center of the palate to avoid contact and gagging. Crosstex has excellent Wrap-Ease Cushions for sensors with barriers. These prevent the mandibular and palatal tori from being injured. They’re also comfortable and easy to use.

Professional swallowers

Think of a sword swallower. I gag just thinking about that, and I’m not a gagger! How did they train themselves not to gag while putting that long sword down their throats? What about people who “swallow” fire or other items mentioned in books like Ripley’s Believe It or Not!

Do these people not have gag reflexes? How do they overcome any gagging? Do they use continuous training such as mind over matter? What about people who are professional eaters? They have to overcome gagging in order to swallow enough food to win a contest. Participants practice in order to put on great shows for audiences. Patients can also practice at home to desensitize their gag reflex.

In the dental office, gagging takes most people out of their comfort zones. Gaggers often don’t want to return for more dental care. Every experience can be traumatic. Treatment is often postponed until it becomes an emergency. Future recare appointments are frequently cancelled due to anticipated stress and fear.

Every office should consider creating a standard operating procedure for these patients. Every team member should learn techniques to make appointments as comfortable as possible. Stress management is a significant step in this process. Patients could practice at home to desensitize their gag reflex each time they brush their teeth.

Gagging is a defense system of the body to prevent choking. I hope this article helps lay this gagging reflex problem to rest. You can collect some little bags of salt to use, and remember, they are infection-control friendly.

Patricia Pine, RDH, COM, is a national and international speaker specializing in OSHA, infection control, lasers, and orofacial myology. Pine conducts in-office trainings, boot camps, online seminars, and lectures at dental/dental hygiene conventions. She is a member of OSAP speaker’s/consultant’s bureau and publishes regularly in several dental magazines. Pat provides both OSHA Boot Camp and orofacial myofunctional therapy. Contact her at info@oshatrainingbootcamp.com.

References

1. https://www.medigoo.com/articles/hyperactive-gag-reflex/

2. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8647679

3. http://www.dentalhygiene411.com/how-to/x-rays-gaggers/